Saturday, October 31, 2009

Memory and Media

Both Lisa Parks and Tom Keenan examine the disparity between visibility of crisis (in both instances human violence & genocide) and actual human intervention, humanitarian aid. Though in former Yugoslavia as within the Darfur, huge media corporations (CNN and Google, respectively) were involved in actively broadcasting the private, localized violence to public and global audiences, the lack of response was similar. People watched, heard, and even at times, were there, yet the violence did not slow.

De Certeau also raises questions that can be linked here, particularly when he writes on page 108: "memories tie us to that place...it's personal, not interesting to anyone else."

What my pulling together of these authors brings into the equation is how collective or cultural (ie. stronger) memory might have influenced the situations Keenan and Parks describe. Was it precisely because the memory of Darfur was neither present nor relevant to viewers that they did not feel compelled to act upon their GoogleMap view? Do media consumers in general need to have or even to feel that a personal connection exists between themselves and what they see (the people being killed, the place being destroyed, etc.)?

[this might in fact also be relevant to the discussion that Pooja lead in our section about the narrativity and personalization of American media-- we discussed it in terms of the problems it raises and the pressure it places on objectivity, but might it also be an incentive for fund-raising or actual, physical intervention??]

Both CNN and Google Maps desensitize violence, they mediate the blood and broken families with digital interfaces. Moreover though, they might also create an odd power dynamic, in which we as watchers, users, listeners are looking down onto these situations. We are naturally distanced from them, but might these interfaces actually widen this distance? Do these technical instrumentalities use intense organization of details to obscure reality for us (de Certeau 96)

These (above) questions perhaps trail in another direction from my original topic: memory and why the necessity to memorialize/ to create collective commitment to places is important -- how is the media here connected? How does the importance of memory shape the media's job or risk its objectivity?

Friday, October 30, 2009

Sunday, October 25, 2009

A Random Post

The Original:

The Parody:

Jordan Carter

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Keenan and the Impossibility of the Real

“As Control Room shows us, what is authentic and real is lost in the multiplicity of representations”

“We live our lives in language and thus in representation…Yet even if the real is hidden, it exists and by inference and patient study, we can make out its shape. Only the most devoted attention to the real can help us make judgments and take actions which are both responsible and efficacious” (Keenan quoting Michael Ignatieff, 91).

As was mentioned in some of the posts for this week (above), in the readings and especially during our discussion in section, the notion of the real and the necessity to grasp or capture it came up repeatedly. It was argued that we are no longer able to maintain a real lived experience (a space that we were once able to occupy), whether it is from a condition of post-modernity, of overexposure, or as a result of the virtual.

However, one finds it necessary to ask, “Was there ever a time when that was possible?”

If we think about the real as the Lacanian Real, then this Real is seen as an impossible real, an unoccupiable point, a space that is irreducible to meaning. Psychoanalysis would tell us that beyond the signifying network, beyond the visual field, there is nothing. There is nothing beyond representation. It is only through the Symbolic Order that we have any ‘lived experience’ and there is (was) never a time when these experiences weren’t mediated. This is what Thomas Keenan seems to be pointing to in “Looking Like Flames and Falling Like Stars.”

In his essay, Keenan responds to critics such as Michael Ignatieff that argue that the use of media technologies during war in Kosovo produced a ‘virtualization of reality’ and made, for its spectators, a sentiment that they “may no longer ‘care enough to restrain and control the violence exercised in their name’” (Keenan, 90). Keenan offers us a rather different reading of the status of the virtual, comparing it to the role and status of language:

“The technologies of communication thus introduce a basic confusion into the analysis, the dissolution of opposition between real and virtual […] Neither real nor simply virtual – it is the reliability, the moral sureness, of this distinction which is withdrawn from us, and which makes our predicament political. This confusion is precisely the condition of any significant decision, and it is the normal state of language” (Keenan, 92).

If we are to make the comparison of the virtual to language in terms of its function in the symbolic, then the evasions and resistances to the virtual and the desire for the real are areas that must be interrogated. Is the discourse of the real and its construction as an unrealized ideal, the way that it seems to function in the excerpts presented in the beginning of this post, symptomatic of a subject’s constant strive for totality? Does resistance to the virtual and the desire for the real become based in a nostalgia that never was, in a loss that was never had? How does the insufficiency of signification construct one’s own subjectivity?

“The fact that it is materially impossible to say the whole truth – that truth always backs away from language, that words always fall short of their goal – founds the subject…The subject is the effect of the impossibility of seeing what is lacking in the representation, what the subject, therefore, wants to see” (Read My Desire, 35).

"...those agents whose behavior it wishes to affect—governments,

armies, businesses, and militias—are exposed in some significant

way to the force of public opinion, and that they are [...] vulnerable

to feelings of dishonor, embarrassment, disgrace, or ignominy.

Shame is thought of as a primordial force that articulates or links

knowledge with action, a feeling or a sensation brought on not

by physical contact but by knowledge or consciousness alone."

"If shame is about the revelation of what is or ought

to be covered, then the absence or failure of shaming is not only traceable

to the success of perpetrators at remaining clothed or hidden in the dark.

Today, all too often, there is more than enough light, and yet its subjects

exhibit themselves shamelessly, brazenly, and openly."

Is this exhibition of what some view as wrong behavior a failure of shame or an absence of the ability to shame? Shaming is an attempt to embarrass or disgrace someone or some group. A wave to the camera acknowledging its position in recording abhorrent acts may seem like a failure of shame. However, does not shame have to come from within? Does not shame work by illustrating some sort of hypocrisy? It can be argued that revelation is not enough to mobilize shame. That one is performing an act they do not want others to see does not presuppose that the act in is thought of as wrong. The audience for which shame is mobilized is and can only be the ones performing the act in question. Shame cannot be mobilized where there is no hypocrisy revealed.

How to read Keenan: the wave vs. the HR campaign

1. Is knowledge irrelevant?

This looks at if the Enlightenment's "mobilizing shame" does not enact change (overexposure)

2. Does evil "acknowledge" itself openly in governments or political political institutions?

While the Serbian forces were the "bad" guys in the Kosovo war (the suppressing of an independent group), I am not sure how the US would "wave" to the camera. Almost all foreign policy actions by the US are justified because they are on the "good" guy's side, and concealment of our actions is necessary only to ensure the bad guys don't spoil our plans (as displayed in "Control Room").

Would we consider the raising of the American flag during the toppling of Sadam's statue, a liberator's faux-pas in the media spectacle planned by the US with, as a half-wave? We caught it on camera knowingly- but were the soliders scared of this knowledge inciting violence or were they shamed?

3. Is this a call for violence?

By using violence and controlling the media, it seems like you can't lose. Colin Powell calls war a political failure, but look at the success of the militant group in "Born in Flames" once they bombed theWTC and took control of the radio waves and TV by force. One can claim that Al-Qaeda bombed the WTC and won the media war at home. Only through violence is either group successful.

4. How can Thomas Keenan write both "Mobilizing Shame" and "Where are human rights?"?

He starts off by talking about the complex relations of human rights within politics, who is using the medium of human rights, and for what purposes, but then poses the following question regarding the Ansar al-Sunna military group:

"What happens when those who... aim to defeat other warriors unconditionally, without mercy- also speak the language of human right?" (68)

I assume he questions how violence and human rights can co-exist for a group. Although the militant group is not a human rights group, we can ask "what if Amnesty International employs a militia to kill those who violate human rights?" And he plays on the odd closeness between states and human right groups, where in the past the two were at odds (imagine the USA military as an enforcer for Amnesty International).

This militant group problematizes what we classically think of as human rights. We assume HRs as a "general pleading" (65) where the "universalization of particulars becomes plausible" (65). There is a local grievance, suffering, and the protection of human rights should apply to a global audience in order to help the particular suffering (no one suffering is less valid than another).

But the militias are playing an odd game of human rights, saying their particular case of suffering deserves attention, but they do not apply their case to a universal audience. They are the Roman plebeians speaking in the public sphere without mimicry- taking up their own cause.

More importantly, to do this speaking, the militant group must control the media and not expose themselves to their support base. This pandering the local without caring too much for a global audience creates a fear of local exposure but a hope for international over-exposure. They took the "rhetorical path" (62) when killingAziz, they did not provide a video tape of hear death, in accordance of Zawahri's calls for no "scenes of slaughter" (61), yet they made sure to release her US issued documentation.

Yet, with the "wave" video from Bosnia, knowledge doesn't play an important role. "With a wave, these policeman announced their comfort with the camera, their knowledge of the actual truth and representation" (446). While the militant group takes pains to define this extremely nuanced defense of what knowledge to put under light and what to hide (who/how to defend and who/how to kill), there is a very different story in front of the camera:

"Here we all know everything and there are no second thoughts, no buts. We know, and hence enact our knowledge, our status, our sense of the complete irrelevance of knowledge. We are the news, information, knowledge, evidence, yes, because we are doing it, making it" (447).

There is a very odd question Keenan approaches, that goes beyond the "politics that hovers between the principles of ethics and the irreversibility of violence." The media demands that the politics either hides violence (the assassination of Aziz, a fear of exposure) or shows the violence (the Serbian looters, a case of over-exposure). The media also demands that we look at ethics in a complex light, where the ethics can be nuanced (a call for particular human rights- better treatment of militia prisoners or that no human rights exist- but still saying killing is OK) or ignored (the needless torching/looting of villages by policeman).

In summary and to the point, how do we work with these two articles together?

A productive sentence to answer this might come from the "Kosovo the First Internet War." "We know more than enough, and yet, somehow, what we know is not finally sufficient" (95).

Media and images, need to be open sites for action, perhaps these are just different ways of acting/performing with media?

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Where is the Control?

While Al Jazeera worded the American news coverage of the Iraq War as “propaganda”, it made me question the function of a national(ized) media. If there is no war without media then there will always be propaganda? If Al-Jazeera does the same thing to its audience (which they did not exactly deny doing) is everything fair and clear? I wanted to find a winner or someone with a moral authority but I quickly learned from this film that that ideology simplifies and idealizes the world. Is our media so impressionable that it can be “hacked”? And if so, does this ability propagate and promote war? Is it truly that simple?

The question of “seeing is believing” was literalized in the film when the bodies of dead Iraqis and American soldiers were shown. I wish I could say it made me uncomfortable but instead I immediately examined my own response. Yes, they were images I had never seen before but there was still a mental block that prevented me from breaking down in the dark classroom. I blamed it on “compassion fatigue” (438). This was not due to overexposure. I fear that all the chatter about disturbing images I definitely “had NOT seen” made me dull to the actual images. In this case, my NOT seeing was enough for believing.

Another interesting part was when CENTCOM prevented the release of their terrorist cards. The obstruction of information which was negated, in part, by this movie, leads to Keenan’s point that “the network ‘treats censorship as damage, and just routes around it.’ That is, if you try to stop the flow of information, all that happens is that you get less information—but nobody else does.” (92) I think the movie made a strong point for how information was disseminated. It was inspiring to the extent the reporters would have fought for access to those cards (and as we all know, eventually, they did acquire the pictures). Maybe our media, when hungry for facts, is not so easily vilified? Gaining information is always the goal but how it is expressed will always be influenced. If we move forward with that understanding, we move in a more positive direction.

Retention of meaning

http://www.mosaiko.gr/admin/articles/images_small/Megatron.jpg

I would like to juxtapose two approaches of mediation: overexposure and classification in excess. Perhaps one could argue that both methods have similar end results.

Overexposure of information corresponds to a waning of affect, a loss of meaning. In Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Jameson mentions artist Nam June Paik’s work as an illustration of how over-stimulation in the form of multiple screens (ex shown above) resulted in loss of meaning of individual parts. In Control Room, I also hear the same sentiment evoked by the Al Jazeera translator who emphasized importance of those who know how to speak softly – what he believed to be a dying breed – in any discourse. I interpreted his comment as an acknowledgement of the failure of overexposure or excessive tactics in media. Shouting a message doesn’t make it more important.

Paradoxically, one could argue that the greater the realm of secret material, the less meaning or inherent interest the classified information holds. The marginal value of the secret decreases with the increased quantity of documents classified as ‘secret’ or ‘top secret.’ Galison highlights how if the “Establishment of Secrecy […] blanket classifies whole domains of learning (nuclear physics, microwave physics), the accumulated mass of guarded data piles up at a smothering rate. It impedes industry, it interferes with work within the defense establishment, and it degrades the very concept of secrecy by applying it indiscriminately” (pg. 241).

In light of such a burden, what is at stake when the government embarks on a “massive effort to recruit AI (artificial intelligence) to automate the classification (and declassification)” (pg. 241)? Does automatically classified information lose yet another level of significance?

Power and the Symbolic

This question is especially interesting, considering Lefort aligns totalitarianism with the symbolic. It is in the order of the symbolic that the individual articulates the self, takes the name of the father. The symbolic order assigns laws--one must not sleep with one's mother--and sever one from nature. One cannot ignore the effect that contemporary media must play within the symbolic order. Media's constant flow of signifiers is a flow directly into the symbolic. Media is strangely absent from Lefort's piece. Though he claims to be concerned with "the most characteristic features of the new form of society. A condensation [. . . taking] place between the sphere of power, the sphere of law and the sphere of knowledge," he never once mentions the means through which this transformation is accomplished (13). It seems to me quite likely that the transformation Lefort concerns himself with is the rise of modern media. As Benedict Anderson articulated about the specific case of print capitalism, modern media has a reciprocal effect on society. Not only is it societal production, but it is the very space in which we conceive of community and society. Lefort refers openly to this production, but never calls it by its name: media. "Economic, technical, scientific, pedagogic and medical facts, for example, tend to be asserted, to be defined under the aegis of knowledge and in accordance with norms that are specific to them. A dialectic which externalizes every sphere of activity is at work throughout the social" (18). While seeming to point away from "media" to something broader, "the social", the very society he describes is one which is constantly becoming more mediatized. How else do we articulate, "externalize" this sort of knowledge? No other way than through our every-expanding range of media: everything from print capitalism to the blog.

Foucault told us that contemporary power does not act through coercion. Contemporary power makes one want to say yes.

"It seems to me that power must be understood in the first instance as the multiplicity of force relations immanent in the sphere in which they operate and which constitute their own organization; as the process which, through ceaseless struggles and confrontations, transforms, strengthens, or reverses them; as the support which these force relations find in one another, thus forming a chain or a system, or on the contrary, the disjunctions and contradictions which isolate them from one another; and lastly, as the strategies in which they take effect, whose general design or institutional crystallization is embodied in the state apparatus, in the formulation of the law, in the various social hegemonies" (The History of Sexuality 93).Our information is not ripped from us, externalized against our will. Rather, we give it up in this constant play of power, in attempts to gain power for ourselves. Furthermore, Foucault is well aware of the conflicts, the constant resistance to power.

Media cannot be modern totalitarianism. In fact, Lefort's discussion of totalitarianism, while an interesting point of departure from which to examine contemporary democracy, leads us in the wrong direction in the analysis of power structures. "The analysis, made in terms of power, must not assume that the sovereignty of the state, the form of the law, or the over-all unity of a domination are given at the outset; rather, these are only the terminal forms power takes" (Foucault 93). It would be more productive to start from the micro level, to examine media and social production.

Media cannot be modern totalitarianism. "The assertion of difference (of belief, opinion or morals) fades in the face of the rule of uniformity; the spirit of innovation is sterilized by the immediate enjoyment of material goods and by the pulverization of historical time; the recognition that human beings are made in one another's likeness is destroyed by the rise of society as abstract entity" (15). Media is the very space of this fading, this sterilization, this pulverization, this destruction. When one shifts their gaze from the macro to the micro, it becomes almost impossible to articulate the specific points of power. The kings and princes all seem to be headless.

Here, I'd like to break from this discussion, and pose a question: what is the most power an individual can have? Who are the supermen of our society, and how do they employ media to maintain their strength? To bring Lefort back into the conversation, "neither the state, the people nor the nation represent substantial entities. Their representation is itself, in its dependence upon a political discourse and upon a sociological and historical elaboration, always bound up with ideological debate" (18). Is the articulated, the "substantial" which has power, or is remaining unsaid, invisible, the key?

The Abolition Movement vs. The Human Rights Movement: Reality vs. The Image

Perhaps the spatial and physical barriers between modern Americas and multinational strife, hinders real action. The image of a slave bound by chains can never incite the same amount of pathos as seeing the physical slave with one’s own eyes. Direct spectators of the slaves’ pain and struggle, abolitionists were able to empathize in a profound manner. Slavery was neither private nor public, it was simply reality. Unfortunately for the present day Human Rights Movement, the image—no matter how realistic or sensational—cannot reproduce reality. It cannot produce the degree of action that true experience can. The dissemination of media propaganda can only link strangers, forming small and self-referential ‘publics.’ The abolitionist movement was a coherent collaboration between people who shared the same physical experience. Each of them had witnessed slavery, not some image blurred by the simulacrum.

Moral Psychologists argue that each individual has a 'radius' of moral obligation. That is, the further a calamity is from the individual, the less likely he is to feel a moral obligation to intervene. Accordingly, human rights activists can disseminate all the sensationally violent images of war they please, but the incident itself will always lie beyond the spatial obligations of the individual subject. Moreover, as they continue to bombard their audience with violent images of war, war becomes more and more of a movie—a property of the fantastical. People become desensitized to the violence, and instead of feeling shame, they feel sheer apathy. It would seem that truly progressive and radical action could only be catalyzed by real experience. The OED defines the verb mediate as “to act as a mediator or intermediary with (a person), for the purpose of bringing about agreement or reconciliation; to intercede with. When there is no intermediary, there is no need for reconciliation. In other words, when A is physically linked to C, there is no need for B.

"I stole from a local store"

Limits of the Media

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

Public and Private

Speaking of the post-modern blur between boundaries, and the reassessment of the real through satire, and because YouTube makes us happy.

Turning and Turning in the Widening Gyre...

http://www.chrisjordan.com/current_set2.php?id=11

Power and Justice

Incredible. For me this highlights the relationship between justice and power, and brings to mind a Foucault quote that's been stuck in my head this week: "The strategic adversary is fascism... the fascism in us all, in our heads and in our everyday behavior, the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us." How is this man able to simultaneously recognize American imperialism's damaging impact on his livlihood and countrymen and their active media work against him while also retaining hopes of joining their oppressive ranks? Power and justice seem to be in opposition to one another.

Lost In The Media

During the war with Iraq, there were so many different sides and point of views saturating all kinds of mediums. Considering the overwhelming amount of images and opinions of the same event, a huge discussion on the war began, within many different regions. Different point of views fed through so many mediums generates a "persuading, and negotiating with, public opinion", which could create divide.

However, what we should consider is, how detrimental is persuasion and negotiation with public opinion really is. While there may not be agreement between different new stations, for example, (which was shown withing Control Room) this doesn't necessarily mean this is an aid to the terrorists. The overexposure and overcoverage of the Iraq War, while giving publicity to the terrorists, also brings about new discussions and questions to the public. Through discussion and questioning, new ideas and opinions can be created in order to develop change in some way, shape or form -- first step towards change, starts with thinking differently.

For example, there was the discussion of the showing of the corpses of American soldiers on the station, Al Jazeera. There was an argument that this kind of showing was disturbing, and inappropriate. However, when Al Jazeera, showed the corpses of innocent civilians that died during a bombing, the reaction was different somehow. There was some sort of disconnect there -- the disturbing pictures of foreign civilians did not arouse the same sympathy from Americans that came about from the viewing of American soldiers. One of the soldiers being interviewed realized this, and was then disturbed by this realization, but at least began thinking differently.

Disagreement among media is most definitely confusing and overwhelming for the public, but possibly necessary in order to give the public most freedom is developing their own original ideas on the subject, versus absorbing propaganda at face-value.

Monday, October 19, 2009

Terrorism, Security and Mediation

Keenan's statements about terrorism's relationship with media - "isn't terrorism always in a codependent relationship with the media; doesn't it - unlike, precisely, a simple military confrontation between two conventional forces - essentially work through public opinion, hearts and minds, and persuasion?" (Keenan 60). Though Keenan chooses not to focus on this in his paper, in light of our screening of Control Room, it is one I would like to address.

If terrorist groups are dependent on the media as Keenan claims, it would seem that all the media attention devoted to the war in Iraq and the larger American ideological War on Terror only draws further attention to the terrorist groups. If one goes back to Anderson, it would seem that terrorism employs one of the same basic tools as nationalism does - print capitalism, now in its 21st century form and inclusive of television and virtual media. Except now, because of the increased transnational flows, the boundaries of the imagined community of the nation are fading.

This reminds me of Arjun Appadurai's book "A Fear of Small Numbers", where he states that terrorism is “a kind of metastasis of war, war without spatial or temporal bounds. Terror divorces war from the idea of the nation”; anyone could be a terrorist, and anyone may be a terrorist’s target as well (Appadurai 92). Print capitalism, once a building block of the nation, now expanded to global capitalism, is thus proposed as being a destroyer of the nation as well. Terrorism's unboundedness - it could be anywhere and everywhere at anytime - creates an instability within us and we channel our uncertainty into fear. The The War on Terror is the political manifestation of this intrinsic fear of the Unknown, and Appadurai claims that the most fearsome of terrorists is the figure of the suicide bomber. As a single person uninhibited by traditional rules of war, political systems and physical boundaries, the suicide bomber could be anyone, and anywhere, and could strike at any time, and it is the mere prospect of his attack that incites fear into civilians. Furthermore, his target can be the civilian, because his intent is precisely to cause as much damage as possible. The Iraq War, so tied to 9/11 and the war on terror, is one fueled by the fear of terrorism and the fear of the suicide bomber is translated into the hyper-awareness of guerrilla attacks. As Control Room shows, the US military is fearful of everyone, evidenced by their compulsion to consider everyone a suspect. It is a war driven by the constant fear of the terrorist.

This new, unbounded, transnational war and the unknowns and uncertainties that is produced is what drives fear. The known, on the other hand, is always mediated. What is known about terrorism, what is known about the Iraq War, is always mediated, and it is the person who is best able to manipulate ("spin") the representation of the situation is the one who is control. The ability to shape discourse is thus power. The US military as portrayed in Control Room is seen to be continually engaging in this battle to manage information and representation when it focuses entirely on Jessica Lynch instead of the invasion of Baghdad, when it targets Abu Dhabi and Al-Jazeera, when it tears down the statue of Saddam and so on. This goes back to last week's readings about secrecy and national security. Secrecy, such as the unwillingness of US military to release the locations of its troops, is key to maintaining national security. As Control Room shows us, what is authentic and real is lost in the multiplicity of representations; going against a realist view of the world (and proposing instead a constructivist construction), power lies not in the actual economic and military might, but in the ability to "spin" the story and manipulate the public's perceptions. The war, as Al-Jazeera's producer says, is about victory, and history is written about the victorious, and victory is symbolized by the toppling of Saddam's statue.

Jeanine

Human RIghts

“We are all governed” — and without seeking to become governors, we intervene,

address those who govern, hold them accountable, act where they refuse. The politics

of human rights is, in this sense, largely a “politics of the governed” — not a project that

aims to govern, precisely not that (67).

If human rights is, by definition, opposed to all forms of governance, and acts where ‘governors’ refuse, are they, fundamentally unattainable?.

Born in Flames elucidates the the problem of human rights by showing the post-liberation ‘Revolutionary’ government (a, at the very least, peculiar combination of the two concepts) as still, fundamentally oppressive to marginalized groups. In the film’s world, did The Party replace, or supplement (both as an addition and substitute), Nationalism (which, as we remember, replaced Nationalism?

Linked Networks

The quote seems easy enough. Lefort is right in rejecting Marx's theory of class difference while accepting the validity of early Marx's societal observations, and we see the re-emergence of reification here. What might not seem so obvious is that it's a reification of one's very self for some sort of value (something which, as Lefort notices, also happens in Communism's totalizing idealism in almost the exact same manner, one for a single symbolic value, the other for one symbolic value (determined by the probability signified by the number) out of many), something far different than the commodity fetishism addressed by Marx. However, this is not the place to unpack this, as there's a rather more difficult question that demands answering first.

I've got to deal with another problem here, one that Lefort doesn't even recognize and skips over with almost

Namely, why is "networks" plural?

First, let us register suprise: on one side of the equation, we have a single body, a citizen (the organ of society, the organ of the publicity), and on the other side, mutliple… locations? What exactly is a network? And why are there so many of them?

Let's start with a very basic definition: a network is a linked series of independent actors (nodes), each one passing output to another node, which takes that output, runs some process on it (which of course, can be determined by the data type or information within the data), and then generates new output, either directed to the first node or an entirely new one. These actors are not "joined," necessarily, but they are "related." This information eventually passes through the entire network depending on the functions of interactions behind nodes and the original output passed in. The behavior of these networks tends to follow rather odd statistical properties.

In use, it's assumed that each network fully contains all of its actors (i.e. there is only a single network in the problem), and that all of these actors are of the same type. For example, in neural network modeling, each node represents a neuron, and every node has the same behaviors. After all, each node is contained in the network of that particular area of the brain, and is always passed the same functions which undergo the same set of internal interactions; how could they evolve new properties, new mechanics if there's no source of new?

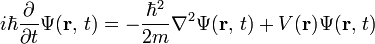

To proceed to the problem of n number of networks, I need to discuss two things. First, Schrodinger's equation. The equation:

While I'll pass over the rather complex details of the equation itself, I'd like to focus on one particular behavior generated by this equation. When multiple wavefunctions are superposed on a single particle, the probability function suddenly becomes time dependent; the actual wavefunction of the particle, the function describing the probability of the particle's location shifts and changes, peaks rising and falling until they reach their starting position, at which point they repeat the cycle all over again.

Second, Systems theory (be warned: I think I'm right in what I say here, but it could be complete bullshit. proceed with caution). A system is a lot like a network; however, where the relation between nodes in a network is often viewed as communicative, incorporeal, lightly abstract, each node retaining its own individual identity, preventing the network from becoming a fully closed body (but not quite; thinking of a network as Deleuze's BwO is more than a bit problematic). Systems, however, eat the parts constructing it to produce some sort of greater body. Ecological systems all have very real interactions occurring between parts; they eat, shit, and fuck one another, constructing the greater body of the ecosystem (forest, ocean, tundra, etc.). Social systems often follow the flow of risk and reward, concrete connections. Organizational Theory subsumes the worker (informational or physical) within the organization at large.

So, in Lefort's construction (which I happen to agree with, for reasons I probably don't have the time to go over here), humans are actors in network*s*. Within each one of these networks, the individual outputs information, and receives transformed output from connected actors, who also pass the output onwards. But, what exactly is at the space connecting these networks, and what sort of result does it have? By connecting these networks together at the site of the body, we have (in effect, due to the same logic as the time-dependent Schrodinger equation) created a time-dependent system, constantly shifting through new sets of probabilities, constantly in flux until the moment of measurement (if you don't understand why I'm calling this a system after somewhat opposing systems and networks earlier, think of it this way: the social/political system is a system whose parts are networks). So, we've found the source of the flux described by so many. But, we have suddenly found a new problem:

If the individual defines themselves in the space of terms passed to them by their community, what happens to this self-definition when one finds themselves in multiple communities/networks? In other words, the problem isn't mere reification; it's a much deeper ideological dissonance that constantly tears the very ego, the very self apart.

At this point, I was thinking I'd mention the work of James Bohman, but getting through all of that took far longer than I thought it would. I also thought I'd bring up the Nietzschian element of the "time-dependent network system," but couldn't really think of it (the looping nature of Schrodinger equation makes it a bit like the eternal return). For those that have struggled through this: thanks for putting up with my bs and/or attempt to both complete an assignment and attempt to define my major at once. To Chun: can you please tell me how much of the Systems Theory stuff I've got right when we meet next week?

(Dis)Locating- Power and Rights

Lefort interested in a "revival of political philosophy," seems to offer a question of what Democracy, as a new form of the constitution of power as exercised by political agencies, marks or changes for the order of society. One of his key principles is that democracy certainly marks a shift in the constitution of power. To explain this Lefort employs an argument that its very familiar to the work of Foucault, a historical view of power prior to the age of revolutions and the implementation of democratic regimes as the modern basis of the political sphere. To do this, like Foucault, Lefort examines power as constituted and defined by the regime of the monarch.

Monarchy for both thinkers marks a certain locality of power, an embodiment in the ruler himself. Lefort posits,

Under the monarchy power was embodied in the person of the prince. This does not mean that he held unlimited power...The prince was a mediator between mortals and gods or, as political activity became secularized and laicized, between mortals and the transcendental agencies represented by a sovereign Justice and a sovereign Reason....[The king's embodied power] therefore gave society a body. (17)This conceptualization is extremely akin to Foucault's observations of the the sovereign monarch, his "double body," and the limits of his power, in the first portion of Discipline and Punish. The point of departure between these theorists is marked by their discussion of power's subsequent dislocation from the body of the king and the regimes that emerge in its absence. For Foucault much of the project is a detailed analysis in the production of knowledge and the systematic formation of a "panopticism" throughout society that marks his work in Discipline and Punish, and the production of varying discourses as subjectivizing systems in History of Sexuality. While Foucault clearly defines power, even as his conceptions of it begins to break from his prior formations, Lefort seems comfortable stopping prior to defining what exactly he means by power in relation to democracy. Rather he posits,

This model [the power formation of the monarch] reveals the revolutionary and unprecedented feature of democracy. The locus of power becomes an empty place....The exercise of power is subject to the procedures of periodical redistributions. It represents the outcome of a controlled contest with permanent rules. This phenomenon implies an institutionalization of conflict. The locus of power is an empty place, it cannot be occupied - it is such that no individual or group can be consubstantial with it - and it cannot be represented. Only the mechanism of the exercise of power are visible, or only the men, the mere mortals, who hold political authority. (17)

While it seems that power as seen in its exercise marks the "institutionalization of conflict," power still seems to be some grand transcendent force that "cannot be represented," but is "exercised." This is not only in disagreement with the Foucaultian argument but seemingly does not say much about democracy. Rather, one of Lefort's final points, that, "democracy is instituted and sustained by the dissolution of the markers of certainty," a "society without a body," seems most important in the constitution of a revolutionary model (19,18). It is interesting to note though, that the principle of "the dissolution of the markers of certainty," also can be seen as the way in which democracy is not only constituted by the means in which it seems to ensure and erase its own abuses of power. Thinking back to Paglen, it is the erasure of these "markers" that seem to be the goal of the classified world.

The other principles of universality and agency serve and important component of Keenan's discussion of the discourse of human rights. There is a structural double bind to this discourse in that the "rights" called for and spoken about are seemingly abstract. Despite this it is a particular instance at which the discourse emerges and this is noted to be at the level of the individual. For Keenan notes "the claim to a right, to something by definition shared with others...is never abstract--it comes from a particular place, experience, existence (whether primary or secondary, to respond to a particular wound" (65). The issue of rights therefore are always offered in response to the relation of an individual or individuals denied or without that "something...shared with others." The double bind or "paradox" is the principle of universality. For Keenan it seems that "the claim [for/to rights] is meaningless if it is not universalizable, but it is effective only if it is rooted concretely" (65).

This marks the position of a complex structure in which, the discourse of rights which emerge from the personal "wound" must be dislocated from the individual in order to be argued on the whole, for all of mankind. This is a problem that confronts the issue of agency. If it is from the wound of the individual that the discourse begins, the individual in their move to achieve the status of becoming legible must sacrifice their own intent. Universality seems to mark a fundamental sacrifice of their own position, a hindrance to their agency to act as a subject in order to dissolve the issue into one that can reach the furthest position. This seems dangerously problematic as the instances in which the discourses of human rights begin are marked at the sites of serious transgressions toward individuals. Perhaps the issue is the defining of right by the category of human. It is not that I am attempting to deny that a humanity exists, but merely that the rights fought for are and should be individual in character, otherwise they seek to threaten the intent of the call for rights. For example I would point to Borden's film Born in Flames, in which the rights of all are put forth before the needs of individuals who are truly oppressed.

I hope we can address some of these issues in class tomorrow.

A man in fatigues hates war? bhwahhh?!

Anonymous and the Secret

Several examples of this phenomenon come to mind. A girl named Sasha Gomez stole a cell phone she found in a cab. When the phone's original owner logged into her online account, she found pictures of Gomez and her instant messenger username. This information, of course, made finding further information easier. After asking Gomez to return the phone over instant messenger failed, someone created a website explaining what had happened with pictures of Gomez. The website began to spread virally, and soon enough a massive network of individuals had obtained her e-mail, social networking pages, and even home address, and a campaign to make her life miserable grew until she returned the stolen phone. Prior to the internet, even if she had been discovered as the thief, it would have been difficult to discern much of Gomez's identity from nothing more than a face and a nickname.

A similar story concerns a teenage boy who posted a video of him abusing his cat, dusty. In the video, he even used a fake name, seemingly to conceal his identity, however, users of the 4chan message board found his identity, and posted his and his parents' personal information, including both home and work addresses and phone numbers, in public places. The cat was relocated and the young man was charged for animal abuse. A related internet group (of sorts) to the 4chan community, known as Anonymous, hacked into Sarah Palin's e-mail account, leading to a good deal of fallout; Time magazine explained that “After [the] hacks were made public, both private accounts were deleted — an act that could technically constitute destruction of evidence. The Alaska governor could also face charges for conducting official state business using her personal, unarchived e-mail account (a crime); some critics accuse her of skirting freedom-of-information laws in doing so. An Alaska Republican activist is trying to force Palin to release more than 1,100 e-mails she withheld from a public-records request.” The lesson, then, is that secrecy is increasingly impossible in an age of modern information technology.

Some secrets are possible to keep, however, even with today's information technology. Secrets, fundamentally, work like algebra problems, where there is a missing piece that must be found. There are secrets which may never be discovered in the same way that there are equations which it is impossible to fully solve. Just as one cannot solve a problem without being able to find the equation, one cannot find a secret when there is no evidence of that secret (one may keep opinions, thoughts, and beliefs entirely secret simply by not expressing them). This sort of secret has little relation to anyone beyond the person who keeps it, and there's not too much reason for anyone to want to find it. The other type of secret which cannot be discovered is one to which there is no answer, or, rather, no single answer. Try and solve the equation 3 + X + Y = 12. Obviously, one may come to solution very easily, discerning X=4 and Y=5; 3 + 4 + 5 =12. Unfortunately, one may also come to the equally valid solution that X=15 and Y=-6. In fact, the possible solutions are literally infinite. Trying to guess at the secret of a magic trick that may be performed in a limitless number of ways, no matter how easy to guess many of those ways are, is nearly impossible. If one guesses one method, the magician can make one incorrect by using another.

This is demonstrated in the power of groups like the aforementioned Anonymous, who, along with loose affiliates, have been or claimed to be responsible for numerous examples of internet vigilantism and “hacktivism,” along with more commonplace bullying and pranksterism; Anonymous describes itself as “the final boss of the internet,” and takes as one of its many slogans that “none of us are as cruel as all of us,” while another reads “Anonymous is a hydra, constantly moving, constantly changing. Remove one head, and nine replace it.” Its strength is in its collective and amorphous nature, which renders any attempt to determine the identity of anonymous entirely futile. When one boy abuses a cat, one girl steals a phone, or one vice-presidential candidate makes an arguably illegal e-mail account, the secret is easy to find; there is a single correct answer. Finding one identity of Anonymous is meaningless because, as another meme states, “Anonymous has no identity.” Without leaders, formal organization, any clear base of operations, or any set, defined membership, Anonymous really does not have, for any practical purposes, an identity.

-Andrew Doty

Where Human Rights Loom Largest

This thread of biopower eventually leads a state, intoxicated by its influence, down a self-destructive road or to be, in Derrida’s words, “more suicidal”. Absurdly, the concept is the principle of killing oneself more. However, as seen in the Patriot Act, and wider still, the Bush Administration’s refusal to act multilaterally with its established allies, the distinction that demarcates the self-state/alliance and the Other become more and more fragile. Aspects of the Other begin to appear within the self (hence the concept of both the enemy within the state, and a distrust of European allies, and a deeper suspicion of potential enemies). Thus if the self includes the Other that threatens, then the state immunes itself by extracting and destroying the Other. But where the Other threatens, the Other is wholly other (“tout autre est tout autre”) as it threatens life itself. However, since the Other exists within the self-state, the state must harm more and more of itself. In this light, the Other can never be fully contained for it exists within the already constituted state[Derrida, Rogues p. 103] - it is ultimately self-harming and self-perpetuating. Unlike the neatly defined Other during the Cold War, this internal struggle creates enemies out of anyone in the struggle for life – suspicions arise even without direct threats and any agent can appear to be a facilitator of harm.

- aaron wee

Beheading the Prince

As I read Lefort, I found it striking that his descriptions of democratic society often agreed with Foucault's formulations; however, Lefort's political theory often seems diametrically opposed to Foucault's genealogies of power. The very opposition of these two theories is intelligible precisely because they converge on similar descriptions of democracies and draw on similar historical progressions (namely, the Prince of the Ancien Régime). How do two thinkers, draw on similar historical periods and arrive at similar descriptions based on two distinctly different methods? More importantly, what are the stakes of these methods?

I'll start by elucidating similarities. Both Lefort and Foucault posit a new form of power in modern society that differs drastically from the monarchy of the Ancien Régime. Both writers also note the centrality of the body of the monarch to the form(s) that power takes in the epoch prior to democratic revolutions. Furthermore, Lefort and Foucault cite the evolution of law to reflect the norm, the power of public opinion, and the influence of statistical thinking in modern societies. Yet these similarities appear on a level of generality that is challenged by the particularities of each author's discourse. For instance, Foucault examines fascism, Stalinism, and liberal democracies alike as partaking in the same strategies and tactics of power, albeit to different extents; Lefort, on the other hand, draws clear distinctions between democratic and despotic governments--they are, for him, different "forms of society."

To analyze different forms of society is the privileged operation for Lefort, the very litmus test of political philosophy, which concentrates on divisions in the social body and on the distinctions between legitimacy & illegitimacy, between truth & falsehood. Political philosophy is thus opposed to crude Marxism, which attempts to describe politics as an epiphenomenon of the economy, and to political science, which reifies politics as a particular sphere of society. According to Lefort, neither Marxism nor political science asks the fundamental question: what are the differences between forms of society?

Lefort argues that the crucial differences between forms of society are to be found on the level of the "symbolic order." While Lefort leaves this order somewhat unelaborated, his description suggests an affinity with the Lacanian Symbolic, implying that the Symbolic Order is a structure that individuals must enter into in order to be a part of society. When Lefort argues that the subject of political philosophy cannot be neutral, he claims that such neutrality does not allow the subject to confront his "implicit conception of relations between human beings and of their relation to the world" that "generat[e] and structur[e]" his experience (12).

According to Lefort, the symbolic order of the Ancien Régime centered on the body of the prince, which constituted a place of power that mediated between the divine and the earthly kingdom. Yet with democratic revolutions, the prince's place is abandoned in the symbolic order, leaving an "empty space." Consequently the spheres of knowledge, law, and power become dissociated, and no group can claim ultimate authority.

Foucault's approach similarly takes up the issue of the body of the prince in the Ancien Régime (in Foucault's parlance, the King's body or the body of the sovereign). In Foucault's analysis the King's body is similarly mystical, at once a physical body and an embodiment of divine authority. Yet for Foucault, democratic revolutions do not simply leave the King's structural position open-ended; instead, new forms of power and knowledge, which are very importantly for Foucault not dissociated, observe, classify, regulate, and discipline individual bodies. Moreover, for Foucault the law comes to function as a norm, not because it is merely separated from absolute authority, but because the complex of power-knowledge comes to usurp the traditional authority of the law.

In short, for Foucault sovereignty is not merely left open-ended by democracy. Instead, the structure of power changes fundamentally, investing both individual bodies and populations with a complex of power, knowledge, and law. Sovereignty is not an appropriate category for Foucault's analysis, for it belongs to juridico-discursive models of power that are too narrowly focused on law and legitimacy, while power itself has moved past the juridico-discursive stage.

Lefort notes that the prince has been surpassed, his position evacuated; yet the "empty place" of the prince in Lefort's theory colors his analysis, inflecting it towards a sort of governing principle or law of forms of society (the symbolic order). While Foucault notes the shift in forms of power from prince to people, his analysis is focused more on tactics and practices of power, rather than on an overarching structure of society. For Lefort, because power and knowledge become disentangled in democracies, the stakes of political philosophy are indeed high: one has the opportunity to speak truth to power. Yet in my opinion, Foucault's theory is more useful because one does not merely protest power with truth, but exercises power by producing discourses. Put metaphorically, Lefort urges us to struggle for the Prince's throne; Foucault insists that we cut off his head.The Use-Agnosticism of Tools

identity and ideology in a democratic society-- is all lost?

Modern democracy, beginning with Tocqueville’s early explorations of Democracy in America, seems to obscure the identity of the individual subject. He writes,

Democracy is instituted and sustained by the dissolution of the markers of certainty. It inaugurates a history in which people experience a fundamental indeterminacy as to the basis of power, law and knowledge, and as to the basis of relationships between self and other, at every level of social life.(19)But unlike a unified totalitarian society, the process of anonymizing the individual is masked by the democratic notion of universal suffrage (everyone counts! But you not a substantial individual, you are a number! (19)), the misunderstood role of the actually anonymous citizen stems from the fiction, as Lefort describes, that the democratic institutions are a set of “delimited” (11) spheres. There is a “double movement” at play, however, that simultaneously hides some dis-junctures/junctures within the framework of democratic society and exposes others. What is at stake in this convoluted conception of the individual and the misunderstood enmeshing of realms in our democratic society?

Lefort, in asserting the flaws in Tocquevilles critique, pinpoints that the positive aspects of democracy society are exactly those with allow political philosophy to flourish in the first place: the “counter-influence is always at work…counteracting the petrification of social life” (16). In a regime such as the Nazi’s in which all think as one according to one ideology, there is little room for counter-influence within the society. Democracy, however, allows for individuals to express themselves “in the face of anonymity” (16). It leaves room for “the rise of demands and struggles for rights that place the formal viewpoint of the law in check” (16) due the bureaucratic organization of balanced government.

How could we take Lefort's analysis to a global level? What does the fact that the Nazi regime, and many other totalitarian regimes, were taken down by outside forces? Perhaps there is some level of people-of-the-world-as-One when it comes to human rights. But then what do we make of Thomas Keenan’s examples of terrorists waving to the camera as they destroy villages? Does that mean that there used to be such a thing and the media has rendered it obsolete? Or does the fact that I even question the existence of a global concurrence on human rights demonstrate the masking of disjuncture that occurs in the democratic institution?

Friday, October 16, 2009

Cameras, Internet, RT@Action?

Twitter was perhaps that which received most coverage namely because its use as a social media site was transformed and also because it prompted a quick reaction from the Iranian government -- proof of its power and threat. Iranian officials were able to track those transmissions made via phones, internet cafes, laptops. People went missing. At this point, however, news of this further corruption spread. The famed immediacy of high-speed internet connections seemed to actually kick in and the local went global perhaps faster than during crises past. Twitter users from around the glove re-tweeted the cries of Iranians, both echoing the crisis and diverting the trackers. Nodes spread forth amongst the web and sites like this even gave instructions on how to maximize the potential of one's Twitter account. The U.S. State Department allegedly asked Twitter to delay its site maintenance work so as to allow the tech-savvy Iranian Twitterers to keep in contact. (Washington Post article, 17.06.09, "Iran Elections: A Twitter Revolution?")

Here, only 10 years after Kosovo's televised and publicized destruction, technology and people's response time seems to have already advanced (albeit only fleetingly). Has this, the example of Twitter and Iran, actually improved the hopes of human rights activists? Has is strengthed ties between local chaos and global intervention? Within the Iranian conflict, people employed their mobile phones, computers, mobile cameras, blogs, social networking sites and more to spread word and reveal the corruption of Iranian law and police forces. The youtube video of the shooting dead of a young woman named Neda in the street during a Tehran protest was seen by millions of people in under 48 hours. Again though, how can the actual effect (barring shock) of this video be measured or quantified?

Is it perhaps due to Twitter's largely (an probably not so happily admitted) decentralized structure word spread so quickly? One vital advantage of Twitter was that rather than a single news source (ie CNN) shooting images of burning villages, here we saw and read and heard of user generated content (though granted, this chaos with the Iranian elections cannot come close in scale to that of Yugoslavia during the late 1990s). News of Iranian elections and corruption was unmediated by Christine Amanpour and instead flowed from the people to the people.

Many questions arise from this example, some as Keenen posed, and others that unique to this situation, concern simple publicity plots to confused actual Iranians, for example. Though Twitter seemed to provide us with the ultimate "close-ups" into the situation, which in turn prompted dozens of mainstream media articles, one wonders what the outcome was in Iran. (Keenen 447) Did the corruption end? Almost certainly not. Has the world moved on? Yes. So though the impact in Iran with Twitter was more exciting, perhaps more global, one must asks if the problem of new media activism has to do less with the local vs. global interests and more with the intensity with which outside nations and human rights organizations are willing and able to commit to strife across the world.

Keeney Quadrangle by Jamal and Jamie

Keeney Quadrangle

Providing “a dignified and happy home for the independents” (The man, the myth, the legend: Barnaby Keeney)

The stately facade of Keeney is effective in masking its drab interior. The 4 arched entryways, fronted by benches, long brick walkways and a well manicured landscape, serve as a welcoming, engaging approach at the ground level properly located on a street called benevolent. On all other sides the quadrangle is gated and raised above ground with 3 entrances atop staircases evenly spaced between the fencing on Charlesfield. It gives one the impression of a gated community projecting an aura of ivy league exclusiveness, sophistication, charm, to the outside community. The inside community is privy to the knowledge that it contrasts sharply with austerity of its interior.

The seemingly endless hallways, cold dimly lit paths within the maze, appear to work against the sense of communities within a community the RPLs of the building attempt to create. Five floors in each of the six connected houses: Walter Goodnow Everett, Walter Cochrane Bronson, John Franklin Jameson, Albert Davis Mead, Raymond Clare Archibald, and William Carey Poland. One third of the freshman class resides here. A space originally intended to house no more than 585 students is now inhabited by 655 people. Lounge and kitchen spaces have turned private to accommodate extra students in the face of overcrowding. This overcrowding caused my the admission of more students this year than ever for fear many students deferring to other schools. The student surplus does not cause to University to let more students live off-campus. Instead, former public spaces have turned private in the name of the financial security. Once the central meeting spaces of the halls --- one on each floor all six --- are now spacious doubles with kitchens for incoming freshman. Within this difficult to navigate maze that is Keeney, are scattered remaining lounges and study spaces tucked away in secret, not meant for the larger brown community.

Upon entering through the door into Archibald house, you see a door on the far side. A sign on the door has a poster of a Unit theme and the names of the students living in this room. The next door is the same, with different names. And the next door, and the next door… All rooms have the same “amenities”

A bed (11.5 inches clearance from the floor) with twin extralong mattress and pillow

A desk and chair

A bookcase

A dresser

A built-in closet

A wastebasket

A recycling bin (shared between roommates)

General room lighting

Having lived here before, I know exactly what is in these rooms. I know the name of the person living here. Walking through the halls, one runs into distinct smells in front of some rooms. White boards are littered with inside jokes, quotes, and the like. With so much information available to me, I can imagine what is inside of these rooms but never actually know. It all feels so familiar. I can identify with this door, unto it I’m able to map my own residential experiences.